How old is that fish?

Comparing age and growth in fish can tell us a lot about the health of Utah fisheries

[Originally posted by Utah Division of Wildlife Resources]

By Chris Penne

Northern Region Aquatic Manager

Have you ever wondered how long it took to grow that big fish you just caught? You’re not alone. Fishery biologists are very interested in answering that question too, and we do a lot of work behind the scenes to find the answer.

Why does this matter? The short answer is that knowing the age of a particular fish — and others in the same population — is the key to determining not only the overall health of a fishery, but how best to manage it. The longer answer may surprise you, and it’s what we’ll delve into in this post.

Determining fish demographics

At some point, you may have participated in a national census. Those surveys help assess changes in the nation’s demographics every decade. Fishery managers also like to take a census of sorts when it comes to various waterbodies. We don’t count every fish, but we do take a large sample every few years to gather information about the different species present, and measure fish age, length, weight and more.

This information helps us monitor the changing demographics of a fishery. For example, when we determine the average age of fish for a given body length, along with the relative number of fish by age groups present, that allows us to estimate aspects of the overall fish population. We can figure out things like the rate at which new fish are being added to the population, mortality rates, as well as how fast we can expect fish to grow to a size that anglers want to catch. That’s some powerful information!

So, how do biologists figure out how old fish are?

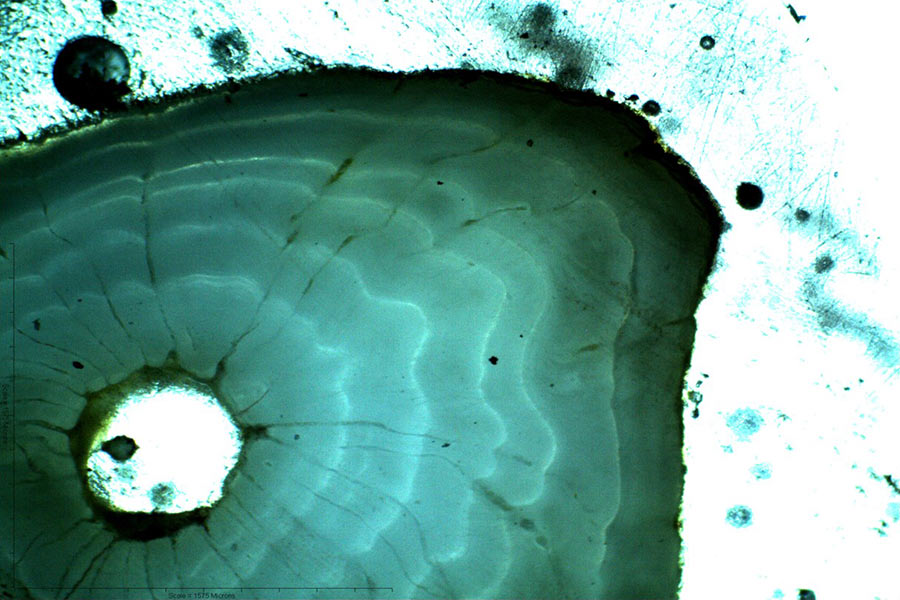

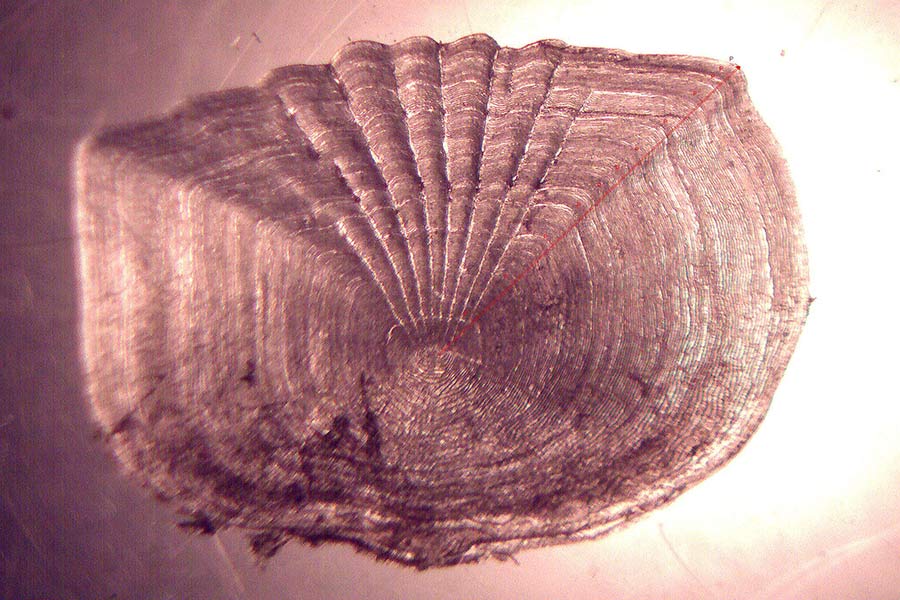

Nature’s calendars and clocks provide many clues to figure out the age of things — if you know how to read them. For instance, you may be familiar with how arborists count tree rings to determine how old a tree is. Fish have similar growth patterns represented in their scales, the rays and spines on their fins, and even ear bones (called otoliths).

Here’s how it works: Fish are always growing, and lay down microscopic new layers of growth daily on their scales, bones, fin spines and rays, otoliths, etc. When fish are growing faster — such as in the summertime when food is plentiful and water temperatures support good fish health — these daily layers of buildup are wider. When fish growth slows in the winter, the layers deposited on these structures are narrower and the layers are stacked more tightly together.

These tighter layers of growth during the slow times form a band that we call an annulus. There is typically one annulus per year in a fish’s life, which gives us a relatively easy way to count how old the fish is.

Measuring with microscopes

I age most fish by looking at their otoliths, the rays and spines on their fins, and sometimes their scales. Some special equipment is involved such as a microscope, low-speed saw and image processing software.

We start with encasing the fish’s otolith or other sample in an epoxy resin to make it stable and rigid. Then, we cut a very thin cross section of the sample using a low-speed saw. We can then study the cross section under a microscope to count the number of annuli present.

The age of a fish is not always clear and can be somewhat subjective, making it part science and part art. To ensure it is mostly science, I often enroll another biologist to independently read the same set of structures and compare them with my results to make sure that the ages we assign are in agreement.

I have nearly two decades of experience aging fish and it’s one of my favorite parts of my job. I’m always fascinated by the variations we can see of the same species living in different waters, and the differences in growth among species throughout the state. For example, fish like tiger muskellunge can grow to 14 inches long in their first year of life, while a largemouth bass typically takes four years to reach the same length! Additionally, the pictures we take of the aging structures can be quite beautiful and are truly works of art. Take a look at these photographs of scales, spines, rays and otoliths, and I think you’ll agree.

Learn more

Here are a couple of my favorite recent pieces involving age and growth of aquatic species:

This Nerdist article describes how scientists recently discovered that bigmouth buffalo (a carp-like fish from the upper Midwest) can live to be much older than expected and are some of the world’s longest-lived freshwater fish.

Check out this investigation by the Radiolab podcast entitled The Times They Are a Changin’. A curious professor compared the number of daily growth bands on modern and ancient corals, which led to the discovery that around 380 million years ago our planet’s years were longer by over 40 days!

Chris Penne

Chris Penne is the regional aquatic manager in the DWR’s Ogden office. As a self-described fish-head, he loves managing fish on the job and then catching them in his spare time.